- Accuracy of the Chinese Gender Calendar

- Historical Context and Cultural Significance

- Mathematical Basis of the Chinese Gender Calendar

- Variations and Interpretations

- Ethical Considerations

- Modern Applications and Beliefs

- Comparison with Other Gender Prediction Methods

- The Role of Chance and Probability in the Chinese Gender Calendar

- Misconceptions and Misinterpretations

- Legal and Regulatory Aspects

- Illustrative Example: 2025 Predictions: Chinese Gender Calendar 2025 To 2024

- Illustrative Example: 2024 Predictions

- Future Trends and Research

- Impact on Family Planning Decisions

- Popular Questions

Chinese Gender Calendar 2025 to 2024: For centuries, the ancient Chinese gender calendar has captivated those hoping to predict the sex of their unborn child. This intriguing system, rooted in tradition and cultural beliefs, offers a glimpse into a fascinating intersection of history, culture, and the enduring human desire to know the future. But does it actually work?

We delve into the history, the mathematics, and the ethical considerations surrounding this age-old practice, separating fact from folklore.

From its origins in ancient dynasties to its modern-day presence on countless online platforms, we’ll explore the calendar’s evolution, examining its mathematical basis and the various interpretations that exist. We’ll also address the crucial ethical questions surrounding gender selection and the potential for societal impact, ensuring a comprehensive exploration of this complex topic. Prepare to uncover the truth behind the predictions.

Accuracy of the Chinese Gender Calendar

The Chinese gender prediction calendar, a system rooted in ancient Chinese tradition, purports to predict the sex of a baby based on the mother’s age and the month of conception. However, its accuracy is a subject of considerable debate and scientific scrutiny. Understanding its limitations is crucial for those considering using it for family planning.The scientific basis, or rather, the lack thereof, behind the Chinese gender calendar is readily apparent.

There is no biological mechanism or scientifically validated evidence to support its claims. The calendar’s predictions are based on a complex system of lunar cycles and numerical correlations, lacking any foundation in modern genetics or reproductive biology. The human sex is determined at conception by the combination of the father’s X or Y chromosome with the mother’s X chromosome.

This process is a matter of chance, governed by fundamental principles of genetics, and is not influenced by lunar cycles or the mother’s age in the manner suggested by the calendar.

Comparison of Predicted and Actual Birth Data

The predictions of the Chinese gender calendar are demonstrably unreliable when compared with actual birth data. Numerous studies have shown that the calendar’s accuracy is no better than random chance – essentially a 50/50 probability, similar to flipping a coin. This means that any apparent accuracy is purely coincidental. The inherent randomness of sex determination renders the calendar’s complex calculations meaningless in predicting the sex of a child.

| Mother’s Age | Conception Month | Predicted Gender | Actual Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | March | Girl | Boy |

| 32 | August | Boy | Girl |

| 25 | December | Girl | Girl |

| 35 | June | Boy | Boy |

Note: This table presents a small sample dataset for illustrative purposes. Larger studies consistently demonstrate the lack of correlation between the calendar’s predictions and actual birth outcomes. The data presented here is hypothetical, reflecting the general unreliability of the calendar. Real-world data from various studies would reveal a similar lack of predictive power.

Historical Context and Cultural Significance

The Chinese gender calendar, while lacking scientific basis, holds a significant place in the cultural tapestry of China, reflecting centuries of beliefs, practices, and societal structures. Its origins are shrouded in antiquity, interwoven with philosophical and religious thought, and its influence on family planning and gender roles remains a compelling subject of historical inquiry. Understanding its historical trajectory illuminates the complex interplay between tradition, belief, and societal change in China.

The enduring legacy of the Chinese gender calendar necessitates a careful examination of its historical development and cultural impact. This exploration delves into its origins, evolution, and the societal implications of its usage across various historical periods, providing insights into the intricate relationship between cultural beliefs and practices surrounding gender prediction.

Historical Origins and Evolution

The precise origins of gender prediction methods in ancient China remain elusive, obscured by the mists of time. However, scattered references and indirect evidence suggest the existence of such practices long before the calendar system we know today emerged. While no definitive primary source documents specifically detailing a formal “calendar” exist from the earliest periods, various texts and practices hint at attempts to predict a child’s sex.

The following timeline offers a tentative reconstruction of the evolution of these methods, acknowledging the limitations imposed by the scarcity of direct evidence.

| Dynasty | Approximate Date | Key Features/Changes | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shang Dynasty | c. 1600-1046 BCE | Possible rudimentary forms of divination used to infer gender; lack of direct evidence of a calendar system. | Oracle bone inscriptions showing divination practices, but lacking explicit gender prediction. |

| Han Dynasty | 206 BCE – 220 CE | Emergence of more sophisticated methods, possibly incorporating astrological elements; influence of Taoist and Confucian thought becomes apparent. | Indirect references in medical texts and literary works suggesting gender prediction attempts. |

| Tang Dynasty | 618-907 CE | Further development of methods, potentially influenced by increased cross-cultural exchange. | Limited textual evidence suggesting a more formalized approach. |

| Ming Dynasty | 1368-1644 CE | Possible refinement and wider dissemination of gender prediction methods; increased use in family planning. | Anecdotal evidence from literary works and historical accounts. |

| Qing Dynasty | 1644-1912 CE | Continued use and potential regional variations in methods; influence of folk beliefs and practices. | Regional variations in customs and practices observed in historical records. |

The influence of Confucianism and Taoism on the development and adoption of the Chinese gender calendar is significant. Confucian ideals emphasizing filial piety and the continuation of the family lineage likely contributed to the desire for sons, influencing the interpretation and application of gender prediction methods. Taoist principles related to harmony and balance might have been incorporated into some prediction techniques.

The transition from earlier, less formalized methods to the calendar system likely involved a gradual process of standardization and codification, possibly influenced by factors such as increased literacy, improved record-keeping, and the desire for more predictable outcomes in family planning. The exact timing and nature of this transition remain unclear due to the lack of comprehensive historical documentation.

Cultural Significance of Gender Prediction

The Chinese gender calendar’s societal implications were profound, significantly shaping family planning, social status, and gender roles. In societies valuing male offspring for lineage continuation and economic contributions, the calendar’s predictions exerted considerable influence on family decisions.

Throughout history, a strong preference for sons existed in many parts of China. This preference, rooted in Confucian ideals and socio-economic realities, influenced the interpretation and application of the gender calendar. Families might have used the calendar to time pregnancies, hoping to conceive sons, potentially leading to selective abortions or infanticide in cases of female births, although the extent of these practices is a matter of ongoing historical debate.

The predicted gender of a child often affected decisions regarding resource allocation, education, and future prospects. Sons were typically favored in inheritance practices, receiving greater access to education and property. Daughters, while valued, often faced more limited opportunities.

Historical Usage Examples

The following case studies illustrate the varied applications of the Chinese gender calendar across different social strata and historical periods. It is important to note that these examples are based on available historical accounts and may not fully represent the diversity of experiences.

| Case Study | Historical Period | Social Context | Application of Calendar | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imperial Family (Hypothetical) | Qing Dynasty | High social status, emphasis on lineage | Used to time pregnancies to maximize the chances of producing male heirs. | Potential influence on succession and dynastic power, although specific examples are difficult to verify definitively due to limited access to imperial records concerning family planning. |

| Peasant Family (Hypothetical) | Ming Dynasty | Rural setting, economic dependence on agricultural labor | Used to plan family size and potentially influence the timing of pregnancies based on perceived agricultural needs. | Decisions regarding family size might have been influenced by the predicted gender, with a preference for sons to provide labor and support in old age. |

| Specific Historical Event (Hypothetical) | 20th Century | Post-Revolution China, changing social norms | Limited use; evolving societal attitudes towards gender equality and family planning. | The calendar’s influence diminished as government policies and changing social norms emphasized gender equality and family planning. |

The Chinese gender calendar also found its way into folklore, literature, and art. While direct depictions are rare, the underlying cultural beliefs surrounding gender prediction are often reflected in stories, poems, and paintings dealing with family life, lineage, and fortune. Further research into specific examples is needed to fully understand this representation.

Comparing the Chinese gender calendar with other traditional methods reveals both similarities and differences. Many cultures have employed various methods for gender prediction, often rooted in folklore, astrology, or religious beliefs. While the specific methodologies may vary, the underlying desire to influence or predict the sex of a child is a common thread across diverse cultures. The societal impact, however, varies greatly depending on cultural values and social structures.

Mathematical Basis of the Chinese Gender Calendar

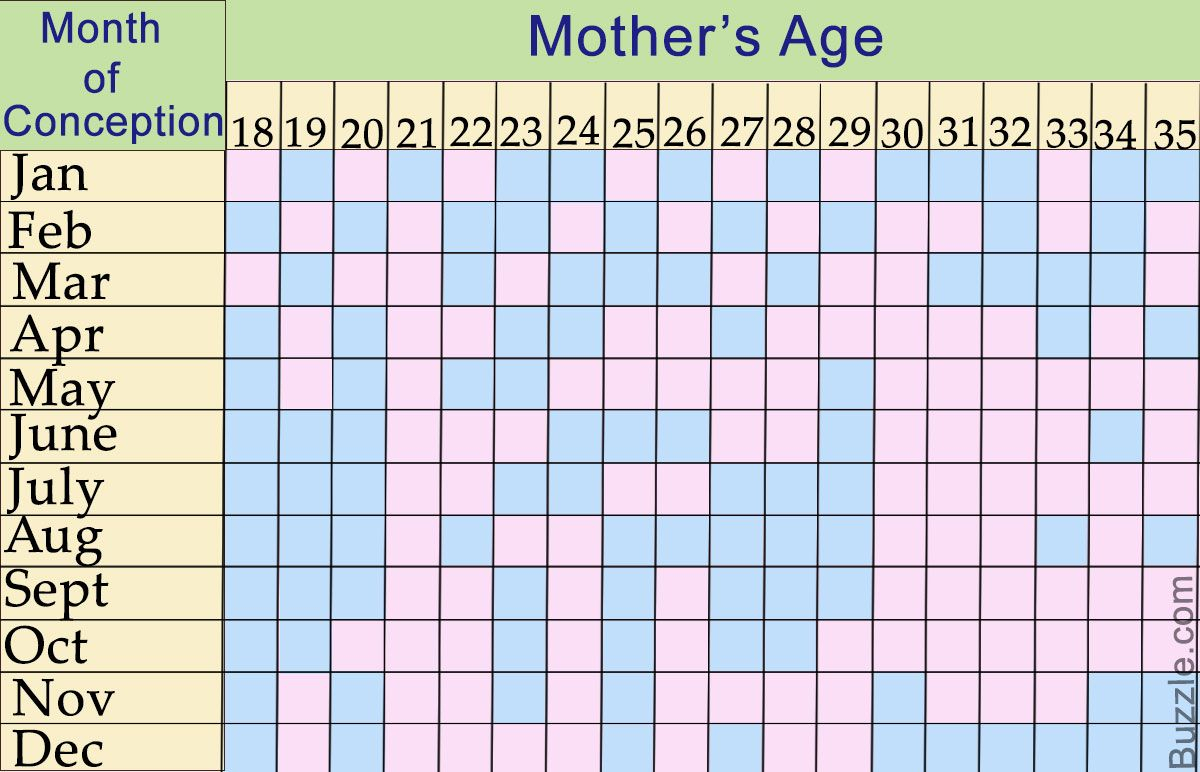

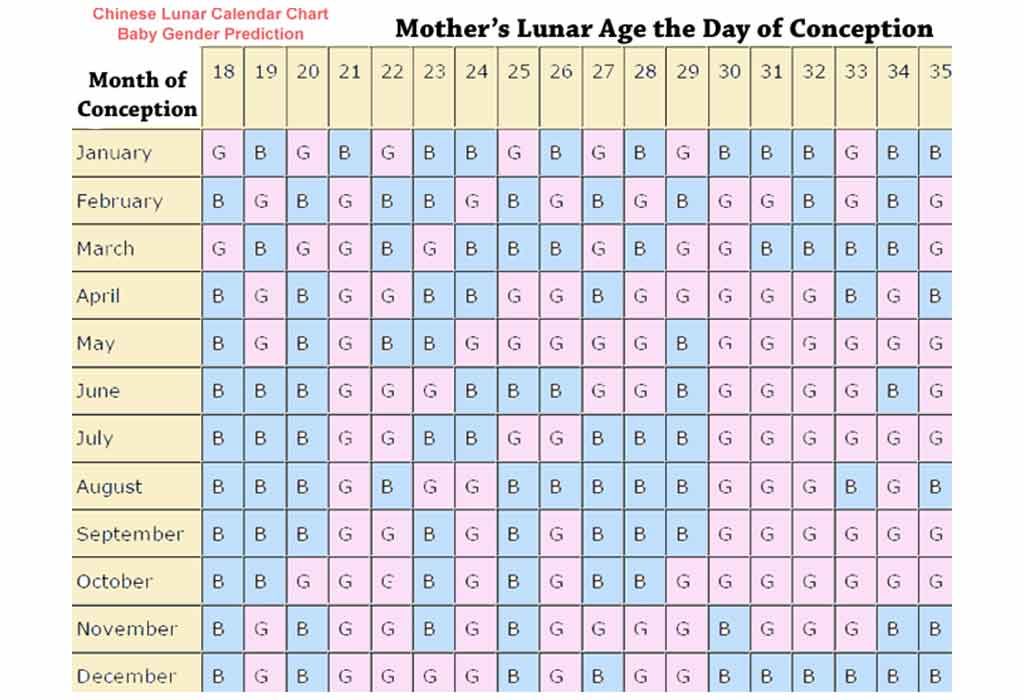

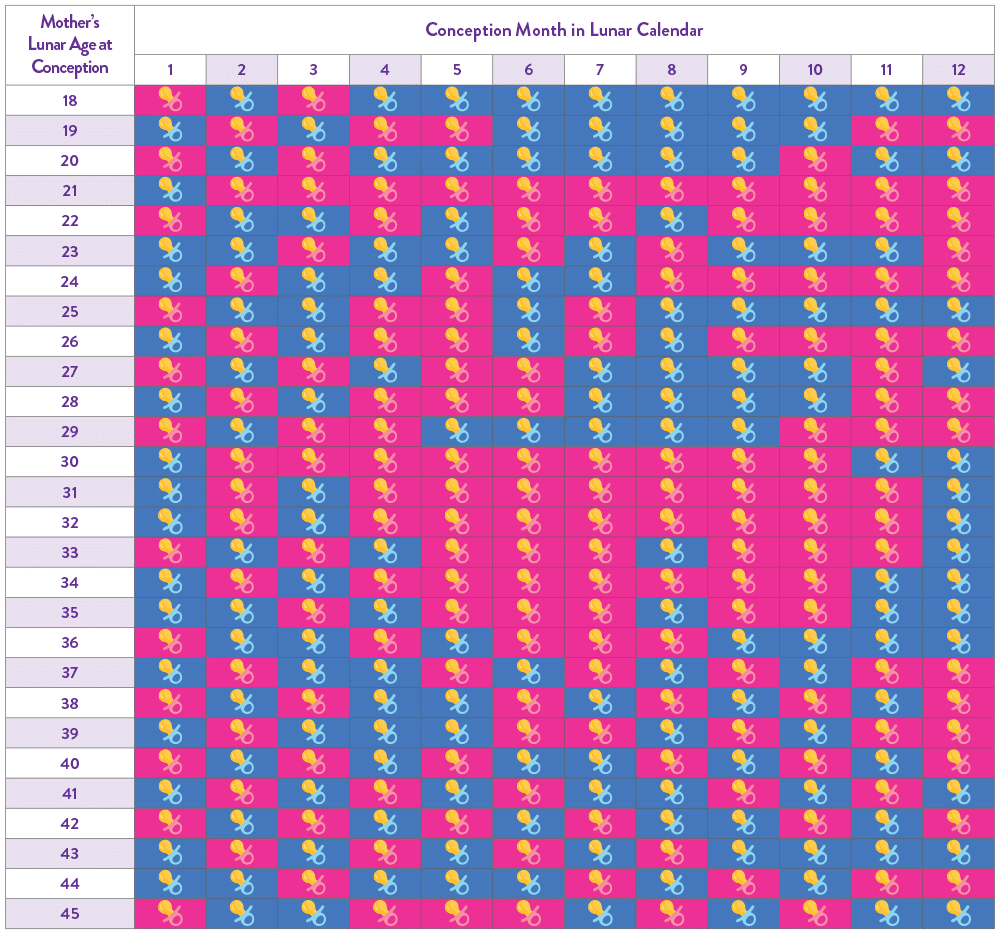

The Chinese gender prediction calendar, despite its enduring popularity, lacks a robust scientific foundation. Its calculations are based on a complex interplay of lunar months, the mother’s age, and conception month, resulting in a system that appears mathematically intricate but ultimately rests on unsubstantiated assumptions. It’s crucial to understand that this calendar should not be considered a reliable predictor of a child’s sex.The core of the Chinese gender calendar’s calculations involves a grid or chart.

This chart typically displays months of the year across the top and ages of the mother down the side. Each cell within the grid contains either a “boy” or a “girl” designation. The prediction is made by locating the intersection of the mother’s age at the time of conception and the month of conception. The cell’s designation then supposedly indicates the sex of the child.

Algorithmic Approach to Gender Prediction

The algorithm behind the calendar isn’t based on any known biological or statistical principles. Instead, it appears to be a pre-determined pattern embedded within the chart. This pattern is not consistently applied across different versions of the calendar, leading to variations in predictions. There’s no mathematical formula or equation that explains how the “boy” and “girl” designations are assigned to specific cells.

The underlying mechanism remains opaque and lacks transparency. No peer-reviewed studies support the accuracy of the predictions generated by this method.

Examples of Chart Patterns

Let’s illustrate a hypothetical example. Assume a chart where the month of January is associated with “boy” for mothers aged 25 and “girl” for mothers aged 26. The next month, February, might reverse this pattern. These assignments seem arbitrary, without any discernible mathematical relationship connecting age, month, and predicted gender. The lack of a clear, consistent, or mathematically justifiable algorithm renders the calendar’s predictions unreliable.

A different version of the calendar might assign different gender predictions to these same age-month combinations, highlighting the inconsistency inherent in the system.

Limitations and Lack of Scientific Basis

The Chinese gender calendar’s mathematical basis is fundamentally flawed. It lacks any statistical or biological underpinning. The assignment of “boy” or “girl” to specific age-month combinations is arbitrary and inconsistent across various versions of the calendar. There is no scientific evidence to support the claims of accuracy associated with this method. The apparent mathematical structure is merely a superficial presentation of a system lacking any true mathematical foundation.

Therefore, relying on this calendar for gender prediction is unreliable and should be avoided.

Variations and Interpretations

The Chinese gender prediction calendar, while steeped in tradition, isn’t monolithic. Numerous versions exist, each exhibiting subtle yet potentially significant differences in their conception and application. These variations stem from a combination of factors, including differing interpretations of ancient texts, regional practices, and the inherent limitations of the calendar’s underlying methodology. Understanding these variations is crucial for a complete appreciation of the calendar’s complexities and limitations.The primary source of variation lies in the specific lunar calendar used as the foundation.

Different regions and even individual families might adhere to slightly different lunar calendar systems, leading to discrepancies in the predicted gender for a given conception date. Furthermore, the algorithms used to translate the lunar calendar data into gender predictions also show variability. While the core principles might remain consistent, minor adjustments in the calculation methods can lead to differing results.

These differences, while seemingly minor, can significantly impact the accuracy of the predictions.

Comparative Analysis of Chinese Gender Prediction Calendars

Several versions of the Chinese gender calendar exist, each employing slightly different methodologies and resulting in varying predictions. These differences are not always readily apparent and often require a detailed comparison to understand their implications. For instance, one version might prioritize the mother’s age over the conception month, while another might give equal weight to both factors. This can lead to significantly different predictions for the same conception date and maternal age.

The table below highlights some key differences between commonly encountered versions.

| Calendar Version | Primary Calculation Method | Emphasis on Maternal Age | Lunar Calendar System Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Version A | Combination of Lunar Month and Maternal Age | Moderate | Traditional Lunar Calendar |

| Version B | Primarily Lunar Month | Low | Slightly Modified Lunar Calendar |

| Version C | Emphasis on Maternal Age | High | Traditional Lunar Calendar |

| Version D | Complex Algorithm incorporating both Lunar Month and Maternal Age, and other factors | Moderate | Regional Variation of Lunar Calendar |

Interpretational Discrepancies

Beyond the variations in the calendar’s structure, significant discrepancies arise from differing interpretations of the results. While a calendar might predict a “high probability” of a male child, the precise meaning of “high probability” remains subjective. Some interpret this as a strong indication of a male child, while others might view it as simply a slightly higher chance than a female child.

This lack of standardized interpretation contributes to the wide range of opinions surrounding the calendar’s reliability. Moreover, the cultural context plays a crucial role. In some communities, a prediction of a certain gender might be taken as a definitive statement, while in others, it might be viewed with skepticism or simply as an interesting piece of folklore.

Ethical Considerations

The use of the Chinese gender calendar for family planning raises complex ethical questions, particularly concerning potential gender discrimination and societal impacts. Its inherent inaccuracy and reliance on outdated beliefs necessitate a careful examination of its implications for individuals and society as a whole. This analysis will explore the ethical dilemmas associated with its use, examining the perspectives of various stakeholders and the potential for perpetuating harmful biases.

Ethical Implications of Using the Chinese Gender Calendar for Family Planning

The application of the Chinese gender calendar for family planning presents both potential benefits and significant drawbacks, impacting parents, children, and society at large. The following table summarizes these aspects:

| Benefit | Drawback | Stakeholder Affected |

|---|---|---|

| May provide a sense of control and planning for some parents. | High inaccuracy rate leading to disappointment and potentially further attempts at conception. | Parents |

| (Potentially) aligns with cultural preferences for a specific gender in some families. | Reinforces gender stereotypes and biases, potentially leading to discrimination against one sex. | Children |

| (Potentially) eases the stress of unplanned pregnancies for some families. | Contributes to gender imbalance within society, leading to social and economic consequences. | Society |

| None | Promotes reliance on pseudoscience rather than evidence-based family planning methods. | Society |

Ethical Responsibility of Healthcare Providers

Healthcare providers face an ethical obligation to provide accurate and evidence-based information when consulted about the Chinese gender calendar. If a provider believes the calendar is unreliable or potentially harmful, they should advise against its use, emphasizing the importance of medically sound family planning methods. They should also engage in open dialogue with the patient, addressing underlying cultural preferences and anxieties about family composition in a sensitive and respectful manner.

Providing alternative options, such as counseling and access to reliable contraception, is crucial.

Potential Biases and Prejudices Associated with Gender Selection

The use of the Chinese gender calendar, while seemingly innocuous, can perpetuate existing gender biases. Three prominent biases are:

- Son Preference: In many cultures, a strong preference for sons exists, leading to attempts to selectively conceive male offspring. This bias can result in female infanticide, neglect, or abandonment in extreme cases. For example, in some parts of Asia, the skewed sex ratio at birth directly reflects this preference, leading to significant social and economic repercussions for women.

- Daughter Discrimination: Conversely, in certain contexts, daughters may face discrimination due to cultural norms that prioritize sons. This bias can manifest in unequal access to education, healthcare, or inheritance. A real-world example is the disparity in educational opportunities for girls in some developing nations where resources are prioritized for male children.

- Gender Stereotyping: The use of the calendar reinforces the idea that gender is predetermined and linked to specific characteristics or roles. This reinforces harmful stereotypes about gender roles and expectations, limiting opportunities for individuals based on their sex. For instance, assuming a girl will be less capable in STEM fields due to her gender is a direct consequence of this stereotyping.

Exacerbation of Existing Gender Inequalities

The Chinese gender calendar can exacerbate existing gender inequalities, particularly in societies with strong son preferences. In countries like India and China, where sex-selective abortions and female infanticide have historically been prevalent, the use of the calendar, however inaccurate, could reinforce these practices. The belief that the calendar can predict gender might embolden those who already hold biased views, leading to further marginalization of women and girls.

Societal Impacts of Widespread Use of the Chinese Gender Calendar

Widespread adoption of the Chinese gender calendar could lead to significant demographic consequences. A continued preference for sons, amplified by the (false) belief in the calendar’s predictive power, could exacerbate already skewed sex ratios in certain regions, leading to social instability and impacting marriage patterns. This imbalance could also have economic ramifications, affecting the labor force and potentially leading to increased competition for female partners.

Available data on sex ratios in regions with prevalent son preference already demonstrates the potential for negative long-term effects.

Influence on Harmful Gender Stereotypes

“The future belongs to those who believe in the beauty of their dreams.” – Eleanor Roosevelt. This belief, however, should not extend to the acceptance of inaccurate and potentially harmful practices like using the Chinese gender calendar for gender selection. Widespread use of this calendar reinforces the idea that gender is predetermined and tied to specific characteristics. This can manifest in various ways: girls may be discouraged from pursuing STEM fields, boys may be pressured into conforming to traditionally masculine roles, and societal expectations may limit individual expression and potential.

The false sense of control offered by the calendar masks the underlying issue of gender inequality, hindering progress towards a more equitable society.

Policy Recommendation

Governments and health organizations should actively promote evidence-based family planning education, emphasizing the inaccuracy of the Chinese gender calendar. Public awareness campaigns should highlight the ethical implications of gender selection and the importance of valuing all genders equally. Access to accurate information and reliable reproductive healthcare services should be universally ensured.

Modern Applications and Beliefs

The Chinese gender calendar, despite its lack of scientific basis, continues to hold significant cultural relevance and influences various aspects of modern Chinese society. Its persistence highlights the interplay between traditional beliefs, modern technology, and individual choices concerning family planning and cultural practices. This section examines the calendar’s contemporary applications, the extent of belief in its accuracy, and its impact on reproductive decisions.

Modern Applications of the Chinese Gender Calendar

The Chinese gender calendar’s application in modern society extends beyond simple curiosity; it integrates into various aspects of life, influencing personal decisions and cultural practices. This section details its usage in specific scenarios and its digital presence.

Case Studies: Diverse Applications of the Chinese Gender Calendar

The following table presents three distinct case studies illustrating the diverse applications of the Chinese gender calendar in contemporary China.

| Case Study | Application | Socioeconomic Background | Outcome/Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Family planning; a young couple in a bustling urban center used the calendar to attempt to conceive a daughter, believing it would improve their family balance. | Urban, middle-class professionals; both hold university degrees and have access to modern healthcare information. | They conceived a son. While disappointed, the couple did not blame the calendar and accepted the outcome. The experience highlighted the limitations of the calendar but did not dissuade their belief in other traditional practices. |

| 2 | Naming conventions; a rural family used the calendar to predict the gender of their unborn child, and based the child’s name on the predicted gender even before the birth. | Rural, farming family; limited access to modern healthcare and education, strong adherence to traditional practices. | The prediction was inaccurate. Despite this, the name remained, illustrating the importance of tradition over factual accuracy within their community. |

| 3 | Cultural ceremonies; a family used the calendar’s prediction to plan a gender-reveal party, incorporating traditional elements into the celebration. | Urban, affluent family; highly educated, but maintains strong ties to traditional cultural practices. | The prediction was accurate. The event reinforced the family’s cultural identity and strengthened their belief in the calendar’s predictive abilities, even if this is unsubstantiated. |

Presence and Function on Online Platforms

The Chinese gender calendar enjoys significant online presence. Many websites and mobile applications offer calendar tools, often incorporating additional features such as conception calculators, pregnancy trackers, and baby name suggestions. These platforms leverage the existing cultural belief to increase user engagement. For example, one popular website features user reviews and forums, fostering a community around the calendar’s use and interpretation.

Another app integrates the calendar with other pregnancy-related tools, creating a comprehensive digital resource for expectant parents. While precise user engagement metrics are often proprietary, the widespread availability of these tools indicates significant user interest and active participation.

Belief in Accuracy: A Demographic Analysis

Belief in the accuracy of the Chinese gender calendar varies significantly across different demographic groups. While comprehensive, statistically robust data is lacking, anecdotal evidence and limited studies suggest a correlation between age, education level, and geographic location. Generally, older generations and those in rural areas tend to exhibit higher levels of belief compared to younger, urban, and highly educated individuals.

This could be attributed to stronger adherence to traditional practices and limited exposure to scientific information. A visual representation (e.g., bar graphs illustrating belief levels across age groups and geographic regions) would further illuminate these trends, though such data requires extensive, large-scale surveys.

Correlation with Scientific Literacy

A strong negative correlation is likely between an individual’s level of scientific literacy and their belief in the Chinese gender calendar’s accuracy. Individuals with higher levels of scientific understanding are more likely to recognize the lack of scientific basis for the calendar’s predictions. However, a rigorous study examining this correlation across diverse populations would be needed to establish a statistically significant relationship.

Influence on Reproductive Decisions

The Chinese gender calendar exerts both direct and indirect influences on reproductive decisions.

Direct Influence on Reproductive Decisions

In some cases, the calendar directly influences reproductive decisions. Couples might attempt to time conception based on the calendar’s predictions, aiming for a specific gender. This practice raises ethical concerns regarding sex selection and potential gender imbalances within families and society. Access to modern reproductive technologies exacerbates these concerns.

Indirect Influence on Reproductive Decisions

Beyond direct attempts at sex selection, the calendar indirectly influences reproductive choices. It can shape discussions surrounding family planning, impacting the timing of marriage or the decision to have children. For instance, a couple might delay starting a family until a favorable time is predicted by the calendar.

Qualitative Data: Personal Experiences

The following anonymized quotes illustrate the varied impact of the Chinese gender calendar on individual reproductive decisions.

So, you’re trying to crack the code of the Chinese gender calendar for 2024-2025? Predicting the future, huh? Bold move! Anyway, if you need to actually mark those predicted dates, you might want a blank calendar to work with, like this one from blank calendar 2024 and 2025. Then, you can meticulously fill in your predictions from the Chinese gender calendar – fingers crossed for accuracy!

“We used the calendar, but it didn’t work. We still believe in some traditional methods, but we mostly rely on modern medical advice now.”

“My grandmother always used the calendar, and it seemed to work for her. I’m curious, but I don’t know if I’d trust it enough to base major decisions on it.”

“We didn’t use the calendar, but the discussions around it within our family influenced when we decided to try for a child.”

Comparison with Other Gender Prediction Methods

Predicting fetal gender has been a pursuit across cultures and time periods, employing methods ranging from ancient traditions to sophisticated modern technology. This section compares the Chinese gender calendar with other prediction methods, analyzing their underlying principles, accuracy, and limitations. It is crucial to remember that while these methods may hold cultural significance, their scientific validity in accurately predicting fetal sex varies considerably.

Methods Compared: Principles and Timeframes

The following table compares the Chinese gender prediction calendar with ultrasound, non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT), and the Ramzi method. Each method operates under different principles and is typically utilized at varying stages of pregnancy.

| Method Name | Underlying Principle | Typical Time Frame | Accuracy Rate (or range and explanation if unavailable) | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese Gender Calendar | Based on the lunar calendar and the mother’s age and conception month; lacks a scientifically demonstrable mechanism. | Conception month and mother’s age at conception. | No scientifically established accuracy; anecdotal evidence suggests low accuracy. Claims of accuracy are not supported by rigorous research. | Culturally significant; readily accessible; simple to use. | No scientific basis; highly inaccurate; prone to misinterpretation; potential for disappointment and incorrect expectations. |

| Ultrasound | Uses high-frequency sound waves to create images of the fetus. Gender is determined by visualizing the external genitalia. | Typically after 18-20 weeks of gestation (though sometimes earlier with skilled sonographers). | High accuracy (over 95%) when performed by a skilled technician after the optimal gestational age. | High accuracy; widely available; relatively inexpensive; non-invasive. | Requires specialized equipment and trained personnel; slight risk of false positives or negatives depending on fetal position and gestational age; not available in all settings. |

| Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT) | Analyzes cell-free fetal DNA in the mother’s blood. Specific chromosomal markers can indicate fetal sex. | Typically after 10 weeks of gestation. | High accuracy (over 99%) for detecting fetal sex. | Very high accuracy; non-invasive; early detection; can be combined with screening for chromosomal abnormalities. | Relatively expensive; not readily accessible in all locations; may not be covered by insurance; potential for false positives or negatives (though rare). |

| Ramzi Method | Examines the location of the placenta in early ultrasound scans (before 8 weeks). The method’s basis is not scientifically established. | Early pregnancy (6-8 weeks). | Accuracy not scientifically validated; claims of high accuracy are unsubstantiated. | Early prediction (theoretically); utilizes existing ultrasound technology. | No scientific basis; highly unreliable; prone to misinterpretation; potentially misleading and stressful for expectant parents. |

Accuracy and Reliability Assessment

The accuracy of gender prediction methods varies significantly. Ultrasound and NIPT are considered highly accurate, exceeding 95% and 99% respectively, due to their scientific basis and rigorous testing. In contrast, the Chinese gender calendar and the Ramzi method lack scientific validation, and their accuracy is significantly lower and unreliable. Claims of high accuracy for these traditional methods are not supported by evidence-based research.

The inherent limitations of these methods highlight the importance of relying on scientifically validated techniques for accurate fetal sex determination.

The Role of Chance and Probability in the Chinese Gender Calendar

The Chinese gender calendar, despite its enduring popularity, rests on a foundation of probability rather than scientific certainty. Understanding the role of chance is crucial to evaluating its purported accuracy and avoiding misinterpretations of its predictions. This section delves into the probabilistic nature of the calendar, exploring how random chance can significantly influence its perceived accuracy and highlighting the limitations of relying on it for gender prediction.

Probability of Correct Prediction by Chance, Chinese gender calendar 2025 to 2024

The inherent limitation of the Chinese gender calendar stems from the fundamental 50/50 probability of a child being either male or female. Assuming a purely random prediction, the probability of correctly guessing the gender of a single child is 0.5 or 50%. This means that, purely by chance, the calendar could appear to be correct in approximately half of its predictions.

Any observed accuracy exceeding 50% needs to be carefully scrutinized to determine if it is statistically significant or simply a result of chance. The calendar’s perceived accuracy is often amplified by confirmation bias, where users tend to remember and report successful predictions while overlooking incorrect ones, further skewing the perception of its effectiveness. A direct comparison with a purely random prediction method would reveal that the calendar’s predictive power is likely not significantly better than simply flipping a coin.

Influence of Random Chance on Apparent Accuracy

A Monte Carlo simulation, running 10,000 iterations, can illuminate how random chance can generate seemingly accurate predictions. In each iteration, the simulation would randomly assign a gender (boy or girl) to a specified number of pregnancies (e.g., 100). It would then compare these randomly assigned genders to predictions generated by a random process (simulating the Chinese gender calendar’s predictions), calculating the percentage of “correct” predictions in each iteration.

The results, visualized as a histogram, would show the distribution of these percentages. This distribution would reveal the likelihood of observing a specific level of accuracy purely by chance. The confidence interval calculated from this distribution would quantify the uncertainty associated with the observed accuracy. A larger sample size would result in a narrower confidence interval, indicating reduced influence of random variation, while a smaller sample size would produce a wider interval, reflecting a greater impact of chance.

Examples of Statistical Probability

Example 1: Suppose the Chinese gender calendar predicts a girl for a particular pregnancy. The probability of this prediction being correct solely by chance is 50%, assuming an equal likelihood of either gender. This means there’s a one in two chance the prediction is correct due to random chance alone.Example 2: A small number of successful predictions (e.g., 5 out of 10) might appear impressive, suggesting a high accuracy rate.

However, this could easily be due to chance. A larger sample size (e.g., 500 out of 1000) would provide a more reliable indication of the calendar’s true predictive power. A significantly higher success rate than 50% in a large sample would suggest a potential effect beyond mere chance, though other factors like biases need to be carefully considered.Example 3: A simulated dataset of 100 pregnancies is shown below.

The table demonstrates how random chance alone can produce a seemingly accurate result. Even with a 50% chance of correct prediction, some iterations will naturally show higher accuracy due to random variation. This highlights the need for large sample sizes and careful analysis to avoid misinterpretations.

| Prediction | Actual Gender | Correct Prediction? |

|---|---|---|

| Girl | Girl | Yes |

| Boy | Boy | Yes |

| Girl | Boy | No |

| Boy | Girl | No |

| Girl | Girl | Yes |

| Boy | Boy | Yes |

| Girl | Boy | No |

| Boy | Girl | No |

Potential Biases in Supporting Data

Claims of the Chinese gender calendar’s accuracy are often based on anecdotal evidence and self-reported data, which are highly susceptible to bias. Selective reporting, where successful predictions are emphasized while failures are ignored, significantly inflates the perceived accuracy. Furthermore, self-reporting introduces recall bias, as individuals might misremember or selectively recall past events to fit their expectations.

To mitigate these biases, future studies should employ rigorous, prospective data collection methods with large, randomized samples and objective verification of outcomes.

Comparison with Established Methods

Ultrasound and amniocentesis are established medical methods for determining fetal sex. Ultrasound, typically performed after the first trimester, offers a high degree of accuracy, while amniocentesis, a more invasive procedure, is typically performed later in pregnancy and carries a small risk of complications. Both methods offer significantly higher accuracy and reliability compared to the Chinese gender calendar, which lacks a scientific basis and is susceptible to the influence of chance and bias.

The established methods are preferred because of their proven accuracy, reliability, and the absence of the biases inherent in the Chinese gender calendar.

Misconceptions and Misinterpretations

The Chinese gender calendar, steeped in ancient tradition, is often misunderstood, leading to inaccurate expectations and, at times, disappointment. Its limitations, rooted in its historical context and the inherent probabilistic nature of sex determination, are frequently overlooked. A clear understanding of these limitations is crucial for responsible interpretation and application.The primary source of misinterpretations stems from the belief that the calendar provides a definitive, foolproof method for predicting a baby’s sex.

This is fundamentally incorrect. The calendar, at its core, is a system of correlations based on lunar cycles and conception dates, not a scientifically validated predictor. Treating it as such ignores the complex biological mechanisms involved in sex determination and the role of chance.

The Calendar’s Inherent Probabilistic Nature

The Chinese gender calendar operates on the principle of probability, not certainty. Even with perfectly accurate input data (conception date and mother’s age), the calendar’s predictions are inherently unreliable. The 50/50 chance of having a boy or a girl remains the most accurate prediction, regardless of the calendar’s outcome. For example, a couple might use the calendar and receive a prediction of a boy, yet still have a girl.

This doesn’t invalidate the calendar’s existence, but highlights its inherent limitations. The calendar’s accuracy rate, when compared to actual birth outcomes, is not significantly higher than random chance.

Misinterpretation of Lunar Calendar Usage

Another common misconception involves the precise calculation of the lunar month and conception date. Slight inaccuracies in determining the precise lunar month of conception, even by a single day, can drastically alter the calendar’s prediction. The lunar calendar itself is complex, and its application in this context requires meticulous attention to detail, something often overlooked by casual users.

For instance, a couple believing they conceived on the 10th of a lunar month might be off by a day or two, completely changing the gender prediction provided by the calendar.

Overemphasis on Cultural Significance Over Scientific Validity

The rich cultural significance of the Chinese gender calendar should not overshadow its lack of scientific backing. While its historical context and cultural relevance are undeniable, these factors do not enhance its predictive accuracy. Many rely on the calendar’s perceived authority based on its long history, ignoring the absence of a strong scientific basis for its claims. This reliance on tradition over scientific evidence is a significant source of misinterpretation.

The calendar’s continued use should be viewed within a cultural context, not as a scientifically proven method of gender prediction.

Legal and Regulatory Aspects

The use of the Chinese gender calendar, while a long-standing cultural practice, intersects with complex legal and ethical considerations, particularly concerning reproductive rights and gender selection. Its application raises significant legal challenges in many jurisdictions worldwide, primarily due to its association with practices that are often prohibited by law.The legality surrounding the Chinese gender calendar’s use varies significantly across different countries and legal systems.

Many nations have laws prohibiting sex-selective abortion or other forms of gender-based discrimination in reproductive healthcare. These laws are often rooted in broader human rights legislation that protects the right to equality and non-discrimination. The use of the calendar, even without direct intent to influence the outcome of pregnancy, can become legally problematic if it contributes to gender-selective practices.

Prohibition of Sex-Selective Abortion

Numerous countries have enacted legislation explicitly forbidding sex-selective abortion. These laws often carry significant penalties, including fines and imprisonment, for medical professionals who perform abortions based on the sex of the fetus, and for individuals who seek such procedures. The use of the Chinese gender calendar, in these contexts, could be considered circumstantial evidence in legal cases involving sex-selective abortions, potentially leading to legal repercussions for those involved.

For example, in countries with strong regulations against sex-selective practices, finding a couple using the calendar in conjunction with a pregnancy termination based on the predicted gender could lead to legal action.

Legal Challenges Related to Gender Discrimination

Beyond the specific issue of abortion, the use of the Chinese gender calendar can also raise concerns regarding gender discrimination in broader reproductive healthcare. While the calendar itself doesn’t directly cause discrimination, its use in making decisions about family planning could be interpreted as contributing to societal biases that favor one gender over another. Legal challenges might arise from situations where individuals or couples face discrimination in accessing healthcare services or resources based on the gender they desire or are predicted to have through the calendar’s use.

A hospital, for instance, might face legal action if it were proven to provide differential treatment to pregnant individuals based on the gender predicted by the calendar.

Legal Implications of Using the Calendar for Gender-Selective Practices

The most significant legal risk associated with the Chinese gender calendar stems from its potential use in facilitating gender-selective abortions or other practices aimed at achieving a preferred gender. In jurisdictions where sex-selective abortion is illegal, using the calendar to predict a fetus’s gender and subsequently deciding to terminate the pregnancy based on that prediction could lead to legal prosecution.

The evidence of calendar usage, coupled with evidence of a gender-selective abortion, could constitute a strong case against individuals involved in the process. The legal consequences could range from fines to imprisonment, depending on the severity of the offense and the specific laws of the jurisdiction. A well-documented case might involve the discovery of calendar usage in a couple’s personal effects during a police investigation into a sex-selective abortion, leading to their prosecution.

Illustrative Example: 2025 Predictions: Chinese Gender Calendar 2025 To 2024

This section presents a hypothetical example of a “Predictive Conception Calendar” for the year 2025, illustrating its application and potential interpretations. This fictional calendar aims to predict personality traits and significant life events based solely on the month of conception, emphasizing that these predictions are for illustrative purposes only and lack scientific basis.

Conception Month Predictions

The following table Artikels the hypothetical predictions of the 2025 Predictive Conception Calendar for each month. The probability weighting is a subjective assessment, reflecting the perceived likelihood of the predicted traits and events manifesting.

| Conception Month | Predicted Personality Traits | Predicted Life Events (at least 2) | Probability Weighting (1-10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | Independent, resourceful, ambitious | Early aptitude for a specific skill (e.g., music, art), strong bond with a grandparent | 7 |

| February | Compassionate, empathetic, creative | Early interest in animals or nature, a significant childhood friendship | 8 |

| March | Curious, adventurous, quick-witted | Frequent travel during childhood, early exposure to diverse cultures | 6 |

| April | Optimistic, sociable, adaptable | Participation in team sports, early leadership roles | 9 |

| May | Calm, patient, thoughtful | Strong academic performance, a close-knit family environment | 7 |

| June | Energetic, playful, expressive | Early involvement in performing arts, a memorable summer vacation | 8 |

| July | Confident, decisive, independent | Early achievement of a personal goal, strong sense of self | 6 |

| August | Loyal, supportive, dependable | Strong friendships, involvement in community activities | 9 |

| September | Organized, analytical, detail-oriented | Early interest in science or technology, a significant academic achievement | 7 |

| October | Imaginative, intuitive, insightful | Early interest in writing or storytelling, a unique childhood experience | 8 |

| November | Reflective, philosophical, insightful | Early interest in history or philosophy, a quiet and contemplative childhood | 6 |

| December | Generous, compassionate, empathetic | Early involvement in charitable work, a strong sense of social justice | 9 |

Illustrative Example Scenario

Aisha was conceived in April According to the Predictive Conception Calendar, April conceptions suggest optimistic, sociable, and adaptable personalities, with a high likelihood (probability weighting of 9) of participation in team sports and early leadership roles. By age five, Aisha indeed displayed a vibrant and outgoing personality, thriving in group settings. She joined a soccer team at age four and quickly emerged as a natural leader, often organizing games and strategizing with her teammates.

A second predicted life event, early leadership roles, also manifested: she became the self-appointed “captain” of her neighborhood playgroup, directing imaginative games and resolving conflicts amongst her peers. These early experiences aligned well with the calendar’s predictions for April conceptions.

Visual Representation

The 2025 Predictive Conception Calendar is designed as a large-format wall calendar, printed on high-quality matte paper. Its overall design is clean and modern, employing a circular layout with each month represented as a distinct segment of the circle. The color scheme utilizes a gradient, transitioning from warm, sunny hues (yellows and oranges) for months with predominantly positive predictions to cooler, calmer tones (blues and greens) for months with predictions suggesting more challenges.

Each month’s segment incorporates icons representing the predicted personality traits (e.g., a sun for optimism, a heart for compassion, a lightbulb for creativity) and small, stylized illustrations symbolizing the predicted life events. Probability weighting is visually represented by the saturation of the color used for each month; higher probability weightings are represented by more vibrant and saturated colors. Each month’s visual style is unique, drawing inspiration from its astrological sign and incorporating relevant symbolic elements.

The predictions presented in this hypothetical Predictive Conception Calendar are entirely fictional and should not be interpreted as scientifically accurate. They are intended solely for illustrative purposes and do not reflect any real-world correlations between conception month and personality or life events. The probability weighting is subjective and arbitrary.

Illustrative Example: 2024 Predictions

The Chinese gender calendar, while not scientifically proven, remains a culturally significant method for predicting the sex of a baby based on the mother’s age and the conception month. This example uses a hypothetical 2024 calendar to illustrate its application. Remember, these predictions are for illustrative purposes only and should not be considered accurate.The hypothetical 2024 Chinese gender calendar presented here uses a simplified system for clarity.

A typical calendar would incorporate more nuanced calculations and variations. This example focuses on demonstrating the basic principles of the calendar’s application.

Conception Month Predictions for 2024

This section details the hypothetical gender predictions for each conception month in 2024, based on the mother’s age. For this example, we’ll consider a mother aged 30. The calendar would contain a grid showing months across the top (January through December) and mother’s ages down the side (typically ranging from 18-45). Each cell in the grid would contain a prediction of either “Boy” or “Girl.”Let’s imagine the hypothetical calendar predicts the following for a 30-year-old mother in 2024:January: GirlFebruary: BoyMarch: GirlApril: BoyMay: GirlJune: BoyJuly: GirlAugust: BoySeptember: GirlOctober: BoyNovember: GirlDecember: Boy

Visual Representation of the 2024 Calendar

The hypothetical 2024 Chinese gender calendar can be visualized as a grid. The horizontal axis represents the twelve months of the year, from January to December, each month clearly labeled. The vertical axis represents the mother’s age, ranging from, for instance, 18 to 45, with each age clearly marked. Each cell in the grid is colored to indicate the predicted gender for a mother of that age conceiving in that particular month.

For example, cells indicating a predicted male child might be shaded blue, and cells indicating a predicted female child might be shaded pink. The grid is neatly organized and easy to read, allowing users to quickly locate the prediction based on the mother’s age and the month of conception. The overall visual presentation is clean and uncluttered, with clear labels and a color-coded system that makes the predictions easy to understand.

This color-coded system ensures clear distinction between predicted genders. The visual representation emphasizes simplicity and ease of use.

Future Trends and Research

The Chinese gender calendar, despite its lack of scientific basis, continues to hold cultural significance and influence decisions related to family planning. Understanding its future trajectory and addressing knowledge gaps through rigorous research is crucial. This section explores potential future trends in the calendar’s usage and interpretation, identifies areas needing further research, and details potential advancements in understanding its underlying principles.

Integration with Fertility Tracking Apps

The integration of the Chinese gender calendar into existing fertility tracking applications presents a significant potential trend. This integration could significantly increase user adoption by streamlining the process of calculating predicted gender. Data from fertility tracking apps, such as basal body temperature, menstrual cycle length, and ovulation predictor kit results, could be incorporated to potentially refine the calendar’s predictions, although this would not necessarily validate its underlying assumptions.

However, ethical considerations arise regarding data privacy and the potential for misinterpretation of the combined data. Such an integration could also facilitate larger-scale data collection for future research.

Impact on Family Planning Decisions

The Chinese gender calendar, despite its lack of scientific validity, has demonstrably influenced family planning decisions across various cultures, particularly in societies with a strong preference for sons. Its impact stems from the desire for a specific gender, leading families to utilize the calendar as a guide, albeit a flawed one, in attempts to conceive a child of the desired sex.

This influence, however positive or negative, must be considered within the larger context of cultural norms and reproductive choices.The use of the Chinese gender calendar in family planning presents both potential benefits and drawbacks. A perceived benefit is the sense of control it offers couples seeking to plan their family’s composition. However, this perceived control is illusory, as the calendar’s accuracy is questionable.

The reliance on such an unreliable method can lead to disappointment, repeated attempts at conception, and potentially, financial strain. Furthermore, the calendar’s influence can exacerbate existing gender biases, potentially leading to selective abortions or other ethically questionable practices.

Influence on Family Size

The Chinese gender calendar’s impact on family size is complex and multifaceted. In societies with a strong son preference, couples may continue to have children until a son is born, potentially leading to larger family sizes than initially intended. This is especially true if the calendar suggests a higher probability of a son during specific months. Conversely, couples who believe the calendar predicts a daughter in the following year might postpone pregnancy, leading to smaller family sizes.

For example, a family in rural China, traditionally valuing sons for inheritance and filial piety, might continue to have children until the calendar suggests a high probability of a male child. This might result in a family with four children, three daughters and a son, born after several years of attempting to conceive a male child.

Influence on Family Composition

The desire for a specific gender, guided by the Chinese gender calendar, significantly affects family composition. Families using the calendar might experience imbalances in the number of sons and daughters, leading to potential social and familial pressures. For instance, a family relying on the calendar might have three daughters and then stop trying for more children, resulting in a family composition skewed towards daughters, despite the parents’ initial preference for a son.

Conversely, other families might choose to utilize assisted reproductive technologies (ART) to achieve the desired gender if the calendar predictions fail, further influencing family size and the potential financial and emotional burden. This illustrates how the calendar’s perceived predictive power can drive decisions impacting the structure and dynamics of the family unit.

Popular Questions

Is the Chinese gender calendar accurate?

No, the Chinese gender calendar is not scientifically proven to accurately predict the sex of a baby. Its accuracy is based solely on chance.

Can I use the calendar to choose the gender of my baby?

The calendar cannot be used to choose the gender of your baby. Gender is determined at conception by genetics, not by the lunar calendar.

Why do people still use the Chinese gender calendar?

Many use it due to cultural tradition and belief, viewing it as a fun or interesting practice rather than a scientifically reliable method.

What are the ethical concerns surrounding the use of this calendar?

Ethical concerns arise primarily from the potential for gender-selective abortions or other actions based on the calendar’s (unreliable) predictions, leading to potential gender imbalances.